Difference between revisions of "Three Body Problem"

Tom Bishop (talk | contribs) |

Tom Bishop (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

'''The problem with the 3-body problem is that it can’t be done, except in a very small set of frankly goofy scenarios (like identical planets following identical orbits).'''}} | '''The problem with the 3-body problem is that it can’t be done, except in a very small set of frankly goofy scenarios (like identical planets following identical orbits).'''}} | ||

| − | ==No General | + | ==No General Solutions== |

Physics Professor Richard Fitzpatrick at the University of Texas [http://farside.ph.utexas.edu/teaching/celestial/Celestialhtml/node79.html says]: | Physics Professor Richard Fitzpatrick at the University of Texas [http://farside.ph.utexas.edu/teaching/celestial/Celestialhtml/node79.html says]: | ||

Revision as of 23:41, 25 April 2019

The Three Body Problem is a four hundred year old problem of mathematics which has its roots in the unsuccessful attempts to simulate a heliocentric Sun-Earth-Moon system.

Due to the nature of Newtonian Gravity, a three body system inherently prefers to be a two body orbit and will attempt to kick out the smallest body from the system—often causing the system to be destroyed altogether. There are a limited range of scenarios in which three body orbits may exist[1]. It is seen that those configurations require at least two of the three bodies to be of the same mass, can only exist with specific magnitudes in specific and sensitive configurations, and exhibit odd loopy orbits that look quite different than the systems of astronomy proposed by Copernicus. The slightest imperfection, such as with bodies of different masses, or the effect of a gravitational influence external to the system, causes a chain reaction of random chaos which compels the entire system to fall apart[2][3].

“ Describing the motion of any planetary system (including purely imaginary ones that exist only on paper) is the subject of a branch of mathematics called celestial mechanics. Its problems are extremely difficult and have eluded the greatest mathematicians in history. ” — Paul Trow, Chaos and the Solar System (Archive)

400 Years of Defiance

In The Physics Problem that Isaac Newton Couldn't Solve (Archive) physics and astronomy professor Robert Scherrer tells us:

“ There's a physics problem so difficult, so intractable, that even Isaac Newton, undoubtedly the greatest physicist who ever lived, couldn't solve it. And it's defied everyone else's attempts ever since then.

This is the famous three-body problem. When Newton invented his theory of gravity, he immediately set to work applying it to the motions of the planets in the solar system. If you have a planet orbiting a much larger body, like the sun, and the orbit is circular, then the problem is easy to solve -- it's something that's done in a high school physics class.

But a circular orbit isn't the most general possibility, and sometimes one body isn't much smaller than the object it orbits (think of the Moon going around the Earth). This more complicated case can still be solved -- Newton showed that the two bodies orbit their common center of mass in elliptical orbits. In fact, this prediction of elliptical orbits really cemented the case for Newton's theory of gravity. The calculation is a lot trickier than for circular orbits, but we still throw it at undergraduate physics majors in their second or third year.

Now add a third body, and everything falls apart. The problem goes from one that a smart undergraduate can tackle to one that has defied solution for 400 years. ”

Newton's Solution

Mathematician and astronomer Issac Newton is credited to have "brought the laws of physics to the solar system."1 To solve the multi-body problems of his system Newton famously invoked divine intervention (Archive):

“ At the beginning of the 18th century, Newton famously wrote that the solar system needed occasional divine intervention (presumably a nudge here and there from the hand of God) in order to remain stable.11 This was interpreted to mean that Newton believed his mathematical model of the solar system—the n body problem—did not have stable solutions. Thus was the gauntlet laid down, and a proof of the stability of the n body problem became one of the great mathematical challenges of the age.

11Newton's remarks about divine intervention appear in Query 23 of the 1706 (Latin) edition of Opticks, which became Query 31 of the 1717 (2nd Edition) edition see Quote Q[New] in Appendix E). Similar 'theological' remarks are found in scholia of the 2nd and 3rd editions of Principia, and in at least one of Newton's letters. In a 1715 letter to Caroline, Princess of Wales, Leibniz observed sarcastically that Newton had not only cast the Creator as a clock-maker, and a faulty one, but now as a clock-repairman (see [Klo73], Part XXXIV, pp. 54-55). ”

1The University of California San Diego credits Newton with providing the laws of physics for the Solar System (Archive):

“ Then came Isaac Newton (1642-1727) who brought the laws of physics to the solar system. Isaac Newton explained why the planets move the way they do, by applying his laws of motion, and the force of gravitation between any two bodies, letting the force decrease with the square of the distance between the two bodies. ”

Henri Poincaré

http://n.ethz.ch/~stiegerc/HS09/Mechanik/Unterlagen/Lecture13.pdf (Archive)

“ 9.2.1 History

In 1885, Poincaré entered a contest formulated by the King Oscar II of Sweden in honor of his 60th birthday. One of the questions was to show the solar system, as modeled by Newton’s equations, is dynamically stable. The question was nothing more than a generalization of the famous three body problem, which was considered one of the most difficult problems in mathematical physics. In essence, the three body problem consists of nine simultaneous differential equations. The difficulty was in showing that a solution in terms of invariants converges (This isn’t likely to happen today - that the birthday of any contemporary world leader is celebrated by a mathematical competition!). Henri Poincare was a favorite to win the prize, and he submitted an essay that demonstrated the stability of planetary motions in the three-body problem (actually the restricted problem, in which one test body moves in the gravitational field generated by two others). In other words, without knowing the exact solutions, we could at least be confident that the orbits wouldn't go crazy; more technically, solutions starting with very similar initial conditions would give very similar orbits. Poincaré's work was hailed as brilliant and he was awarded the prize.

But as his essay was being prepared for publication in Acta Mathematica, a couple of tiny problems were pointed out by Edvard Phragmn, a Swedish mathematician who was an assistant editor at the journal. Gsta Mittag-Leffler, chief editor, forwarded Phragmn's questions to Poincaré, asking him to fix up these nagging issues before the prize essay appeared in print. Poincaré went to work, but discovered to his consternation that one of the tiny problems was in fact a profoundly devastating possibility that he hadn't really taken seriously. What he ended up proving was the opposite of his original claim. Three-body orbits were not stable at all. Not only were the orbits none periodic, they didn't even approach some sort of asymptotic fixed points. Now that we have computers to run simulations, this kind of behavior is less surprising, but at the time it came as an utter shock. In his attempt to prove the stability of planetary orbits, Poincaré ended up inventing chaos theory. ”

Ask A Mathematician

https://www.askamathematician.com/2011/10/q-what-is-the-three-body-problem/ (Archive)

“ Q: What is the three body problem?

The three body problem is to exactly solve for the motions of three (or more) bodies interacting through an inverse square force (which includes gravitational and electrical attraction).

The problem with the 3-body problem is that it can’t be done, except in a very small set of frankly goofy scenarios (like identical planets following identical orbits). ”

No General Solutions

Physics Professor Richard Fitzpatrick at the University of Texas says:

“ We saw earlier, in Section 2.9, that an isolated dynamical system consisting of two freely moving point masses exerting forces on one another--which is usually referred to as a two-body problem--can always be converted into an equivalent one-body problem. In particular, this implies that we can exactly solve a dynamical system containing two gravitationally interacting point masses, because the equivalent one-body problem is exactly soluble. (See Sections 2.9 and 4.16.) What about a system containing three gravitationally interacting point masses? Despite hundreds of years of research, no useful general solution of this famous problem--which is usually called the three-body problem--has ever been found. ”

The Three-Body Problem (Archive)

by Z.E. Musielak1 and B. Quarles2

“ In the three-body problem, three bodies move in space under their mutual gravitational interactions as described by Newton’s theory of gravity. Solutions of this problem require that future and past motions of the bodies be uniquely determined based solely on their present positions and velocities. In general, the motions of the bodies take place in three dimensions (3D), and there are no restrictions on their masses nor on the initial conditions. Thus, we refer to this as the general three-body problem . At first glance, the difficulty of the problem is not obvious, especially when considering that the two-body problem has well-known closed form solutions given in terms of elementary functions. Adding one extra body makes the problem too complicated to obtain similar types of solutions. In the past, many physicists, astronomers and mathematicians attempted unsuccessfully to find closed form solutions to the three-body problem. Such solutions do not exist because motions of the three bodies are in general unpredictable, which makes the three-body problem one of the most challenging problems in the history of science. ”

As we read above, there are no general solutions to the Three Body Problem. As Ask A Mathematician told us above, the only solutions require very specific, odd scenarios.

A Thousand New Solutions

From a New Scientist article titled Infamous three-body problem has over a thousand new solutions (Archive):

“ The new solutions were found when researchers at Shanghai Jiaotong University in China tested 16 million different orbits using a supercomputer.

...

Perhaps the most important application of the three-body problem is in astronomy, for helping researchers figure out how three stars, a star with a planet that has a moon, or any other set of three celestial objects can maintain a stable orbit.

But these new orbits rely on conditions that are somewhere between unlikely and impossible for a real system to satisfy. In all of them, for example, two of the three bodies have exactly the same mass and they all remain in the same plane.

Knot-like paths

In addition, the researchers did not test the orbits’ stability. It’s possible that the tiniest disturbance in space or rounding error in the equations could rip the objects away from one another.

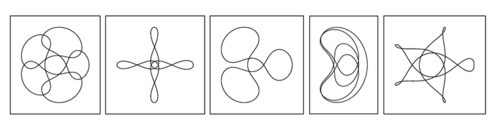

“These orbits have nothing to do with astronomy, but you’re solving these equations and you’re getting something beautiful,” says Vanderbei.

...

Aside from giving us a thousand pretty pictures of knot-like orbital paths, the new three-body solutions also mark a starting point for finding even more possible orbits, and eventually figuring out the whole range of winding paths that three objects can follow around one another.

...

“This is kind of the zeroth step. Then the question becomes, how is the space of all possible positions and velocities filled up by solutions?” says Richard Montgomery at the University of California, Santa Cruz. “These simple orbits are kind of like a skeleton to build the whole system up from.” ”

As suggested, the field of Celestial Mechanics is still on step zero—the stone age. The found orbits are nothing like heliocentric astronomy and there will be an attempt to use them as a skeleton to "build the whole system up from."

Two Bodies of Equal Mass

The research group with the super computer published another study titled: Over a thousand new periodic orbits of a planar three-body system with unequal masses (Archive). The group found only configurations where two bodies had the same mass.

“ Abstract

The three-body problem is common in astronomy, examples of which are the solar system, exoplanets, and stellar systems. Due to its chaotic characteristic, discovered by Poincare, only three families of periodic three-body orbits were found in 300 years, until 2013 when Suvakov and Dmitra ˇ sinovi ˇ c ( ´ 2013, Phys. Rev. Lett., 110, 114301) found 13 new periodic orbits of a Newtonian planar three-body problem with equal mass. Recently, more than 600 new families of periodic orbits of triple systems with equal mass were found by Li and Liao (2017, Sci. China-Phys. Mech. Astron., 60, 129511). Here, we report 1349 new families of planar periodic orbits of the triple system where two bodies have the same mass and the other has a different mass. None of the families have ever been reported, except the famous “figure-eight” family. In particular, 1223 among these 1349 families are entirely new, i.e., with newly found “free group elements” that have been never reported, even for three-body systems with equal mass. It has been traditionally believed that triple systems are often unstable if they are non- hierarchical. However, all of our new periodic orbits are in non-hierarchical configurations, but many of them are either linearly or marginally stable. This might inspire the long-term astronomical observation of stable non-hierarchical triple systems in practice. In addition, using these new periodic orbits as initial guesses, new periodic orbits of triple systems with three unequal masses can be found by means of the continuation method, which is more general and thus should have practical meaning from an astronomical viewpoint. ”

Hill's Region

Astronomer and mathematician George William Hill studied the Three Body Problem. The only way Hill was able to make any progress at all was by using the Restricted Three Body Problem, where one of the bodies was of zero or negligible mass. Even then, the body was still chaotic. The only benefit of the Restricted Three Body Problem and the Mass-less moon is that the moon is no longer ejected from the system, as it usually was. It is confined to what is known as "Hill's Region".

From http://www.scholarpedia.org/article/Three_body_problem (Archive):

The above depicts the crazy and chaotic moon. It even makes a u-turn in mid orbit.

From the text that accompanies the image:

“ The simplest case:

It occurs when, the Jacobi constant being negative and big enough, the zero mass body (we shall still call it the Moon) moves in a component of the Hill region which is a disc around one of the massive bodies (the Earth). This fact already implies Hill's rigorous stability result: for all times such a Moon would not be able to escape from this disc. Nevertheless this does not prevent collisions with the Earth. ”

"Zero mass body" -- One of the bodies in the restricted three body problem is of zero mass.

"Nevertheless this does not prevent collisions with the earth" -- It's still chaotic, even in that simplified version.

One sees that Newtonian Mechanics most certainly does not naturally default to the heliocentric system of Copernicus.

Poliastro

Poliastro, an astrodynamics software developer, shares several numerical methods for the restricted three body problem:

https://twitter.com/poliastro_py/status/993418078036873216?lang=en (Archive)

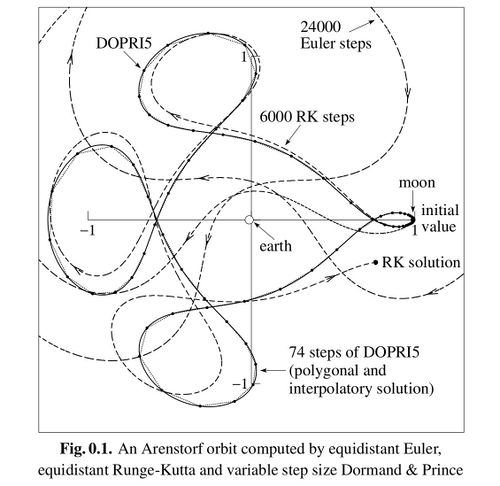

“ Look at this beautiful plot of several numerical methods for the restricted three body problem taken from Harier et al. "Solving Ordinary Differential Equations I". The use of high order Runge-Kutta methods is pervasive in Celestial Mechanics. Happy Monday! ”

Arenstorf orbits are the knotted closed trajectories which are the result of Restricted Three Body Problem solutions.

Chaos Theory: A Demo

The available solutions to the Three Body Problem, beyond being unlike anything seen in Heliocentric Theory, are so sensitive that the slightest change or imperfection will tear the entire system apart. From 'Mathematics Applied to Deterministic Problems in Natural Sciences' we read another account of Poincaré's discoveries:

“ As Poincaré experimented, he was relieved to discover that in most of the situations, the possible orbits varied only slightly from the initial 2-body orbit, and were still stable, but what occurred during further experimentation was a shock. Poincaré discovered that even in some of the smallest approximations some orbits behaved in an erratic unstable manner. His calculations showed that even a minute gravitational pull from a third body might cause a planet to wobble and fly out of orbit all together. ”

The orbits are incredibly sensitive. As a very illustrative demonstration, take a look at this online Three Body Problem simulator that uses the simplest possible figure eight pattern, which requires three identical bodies of equal mass that move at very specific momentum and distance in relation to each other.

Demo: Figure-Eight Three Body Problem

Adjust the slider values in the upper left to something very slight to find what happens. What you will see is a demonstration of Chaos Theory. Any slight modification to the system creates a chain reaction of random chaos.

This is precisely the issue of modeling the Heliocentric System, and why its fundamental system cannot exist. Only very specific and very sensitive configurations may exist. The slightest deviation, such as with a system with unequal masses, or the minute influence from a gravitating body external to the system, will cause the entire system to fly apart. The reader is invited to decide for his or her own self whether those scenarios would occur in nature as described by popular theory.

N-Body Solution Galleries

Below are links to galleries of various Three Body Problem solution galleries. One should note the lack of heliocentric orbits and mass restrictions.

Wolfram Science

https://www.wolframscience.com/nks/notes-7-4--three-body-problem/ (Archive)

“ In Henri Poincaré's study of the collection of possible trajectories for three-body systems he identified sensitive dependence on initial conditions (see above), noted the general complexity of what could happen (particularly in connection with so-called homoclinic tangles), and developed topology to provide a simpler overall description. With appropriate initial conditions one can get various forms of simple behavior. The pictures below show some of the possible repetitive orbits of an idealized planet moving in the plane of a pair of stars that are in a perfect elliptical orbit. ”

Institute of Physics Belgrade

http://three-body.ipb.ac.rs/ (Archive)

n-Body Choreographies

http://rectangleworld.com/demos/nBody/ (Archive)

Scholarpedia.org

http://www.scholarpedia.org/article/Three_body_problem (Archive)

Euler Math Toolbox

http://euler.rene-grothmann.de/Programs/Examples/Three-Body%20Problem.html (Archive)

Supercomputing Challenge

Programming students participated in the New Mexico Supercomputing Challenge to simulate the solar system and found issues with creating basic orbits:

Simulation of Planetary Bodies in the Universe (N-Body) (Archive) (Source Code)

“ Our solar system is an N-body system. N-body simulation is the simulation of astral bodies under gravity, using laws of classical mechanics to define how the astral bodies move. The goal of our project is to model the N-body problem in NetLogo. Code defining how astral bodies interact implements the inverse square law and a gravitational constant to calculate gravitational force between them.

...

Verification and Validation

Even though our model is not entirely accurate, it recreates with graphical simplicity and mathematical correctness of the N-body simulation. Through many many trials, we realize that normal orbits are incredibly complex and hard to obtain through any normal means, and causes us to conclude that our own solar system is an incredible anomaly of the universe. ”

The PDF report explains with additional details that all attempts at observing orbit were unsuccessful.

Universe Sandbox 2

Universe Sandbox 2 (Universe Sandbox ²) is a physics based space simulation developed and published by Giant Army. It has often been claimed that this simulation provides evidence that the Sun-Earth-Moon System and the Solar System are able to be simulated with Newtonian Gravity.

The reader should read the following from a developer blog post and decide whether the program is using a full simulation of gravity:

Working Through the N-Body Problem in Universe Sandbox ² (Archive)

“ By default, the simulations in Universe Sandbox ² try to set an accuracy which prevents orbits from falling apart due to error. This means setting a maximum error tolerance for each step and also making sure the total error doesn’t reach an upper limit.

If you crank up the time step, the simulation then has to take fewer, larger steps. This means the potential for greater error. And the greater the error, the more likely it is that an orbit, which otherwise would be stable, falls apart. Moons crash into planets, Mercury gets thrown out of the solar system — things like that.

This isn’t what most people want in their simulations. But at the same time, most people also don’t want a limit on how fast they can run their simulation. This is a problem.

An imperfect solution

So how can we get around this problem? How can we accurately simulate thousands of objects while still allowing for large steps forward in time? For example, what if you wanted to simulate our solar system on a time scale of millions of years per second so that you could see the evolution of our Sun?

One solution proposed by Thomas, our physics programmer, is to allow for a special mode within simulations running at high time steps. This mode (which of course could be toggled) would collapse the existing n-body simulation into a series of 2-body problems: Moon & Earth, Earth & Sun, Europa & Jupiter, Jupiter & Sun, etc.

Solving a 2-body problem is much easier than solving an n-body problem. Not only is it faster computationally, but there is also a relatively arbitrary difference between figuring out where the two objects will be in one year and where they’ll be in a million years — it still requires just one calculation. So if you collapse an n-body simulation into a series of two-body problems, the simulation could take one big step forward, instead of taking the small steps needed for calculating it as an n-body problem.

The results won’t be entirely accurate, as this method would effectively ignore all gravitational influences outside of the main attractor. As mentioned before, calculating Earth’s orbit by looking at how it interacts with just the Sun is not accurate, as Earth is also affected by every other body. The Sun, however, is the most significant factor by far, because it is much more massive than any other object in our solar system. The other, much smaller forces tend to have little effect overall in non-chaotic systems. So while it’s not correct, it’s close enough when simulating something relatively stable like our solar system. ”