Difference between revisions of "Electromagnetic Acceleration"

Tom Bishop (talk | contribs) |

Tom Bishop (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

[[Category:Sun]] | [[Category:Sun]] | ||

[[Category:Moon]] | [[Category:Moon]] | ||

| − | [[Category:Electromagnetic | + | [[Category:Electromagnetic Acceleration]] |

Revision as of 06:03, 30 June 2019

The theory of the Electromagnetic Accelerator (EA) states that there is a mechanism to the universe that pulls, pushes, or deflects light upwards. All light curves upwards over very long distances. The Electromagnetic Accelerator has been adopted as a modern alternative to the perspective theory proposed in Earth Not a Globe.

Sunrise and sunset happen as result of these upwardly curving light rays.

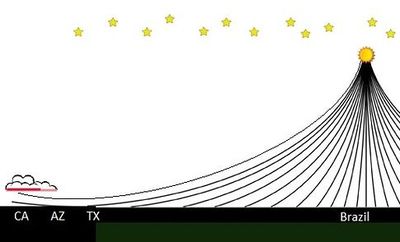

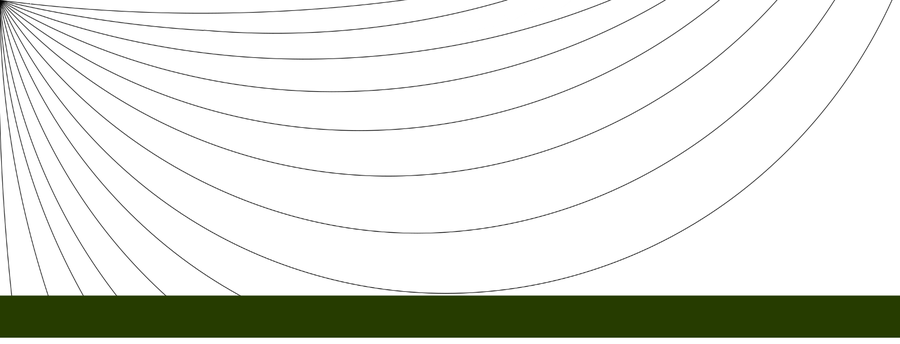

The above illustration depicts rays from the sun which intersect with the earth. Other rays not depicted may miss the earth and make a "u-turn" back into space.

It is believed that the bending of light does not simulate or match the globe curvature. Instead, the bending occurs more gradually over a greater distance. This is why observers can see further than they should in the classic Flat Earth water convexity experiments that take place on shorter ranges near sea level, and why the dip of the horizon at higher altitudes over longer ranges sits higher than the globe earth prediction but lower than a planar prediction (See: Evidence for Electromagnetic Acceleration).

Mechanism

One may point out that it would be quite unreasonable to assert that a particle or wave in motion would travel forever through the universe in a perfectly straight line, unperturbed by any of the variety of forces or phenomena which fills existence. Get into a car and attempt to drive in a perfectly straight line down a highway without turning the steering wheel left or right. It is a near impossible thing to do. The car is affected by the slope and texture of the terrain, alignment of your wheels, the wind, &c. An apparently straight heading turns into a curved one. When it comes to bullets, airplanes, et all, it is expected that bodies never realistically travel straightly. Straight line trajectories rarely, if ever, occur in nature.

While the mechanism which affects light over long distances is not known, the cosmological theme of upwards acceleration fits in with this Flat Earth model.

Articles of Interest

- Light Bends Itself Around Corners - Physicsworld.com

- Stanford Researchers Use Synthetic Magnetism to Control Light

Terrestrial

Clouds Lit From Underside

Rays which miss the earth will turn back up into space, and may hit the underside of clouds before sunrise or after sunset, giving them a reddish glow.

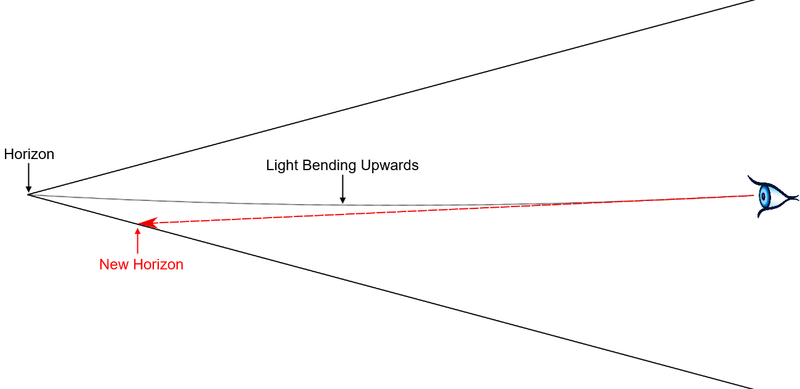

Horizon Dip

The Electromagnetic Accelerator predicts that at high altitudes where one can see further into the distance, the horizon will dip below eye level. Light which travels parallel from the limits of vision will be pulled upwards and miss the eye of the observer. The rays the observer will see are those rays which are transmitted at a lower angle and pulled upwards to meet the observer, resulting in a horizon which is slightly below eye level.

Celestial

Nearside Always Seen

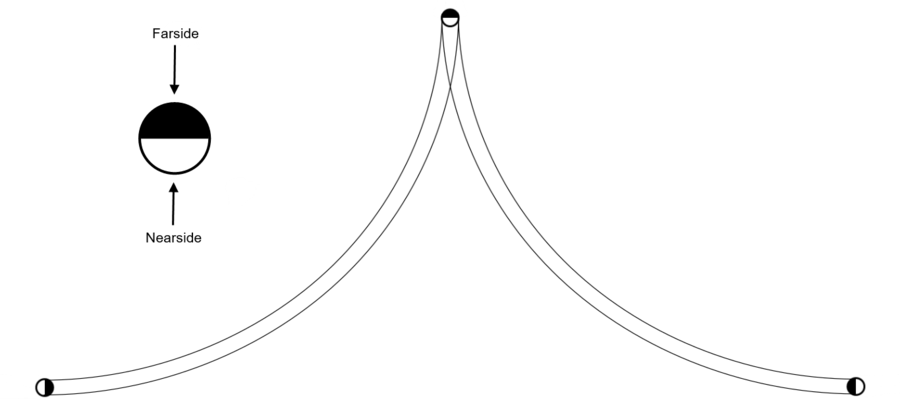

A consequence of this paradigm of upwardly bending light is that the observer will always see the nearside (underside) of the celestial bodies. The below image depicts the extremes of the Moon's rising and setting. The image of the nearside face of the moon is bent upwards around the moon and faces the observers to either side of it.

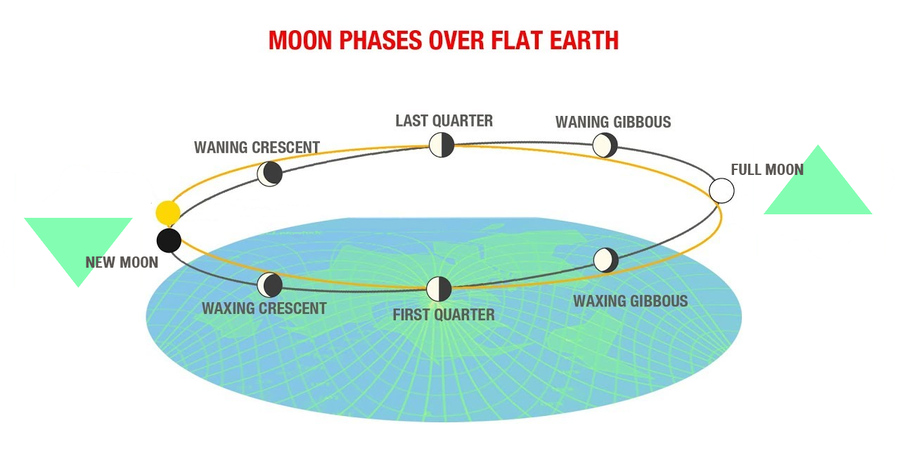

Lunar Phases

When one observes the phases of the Moon they are seeing the Moon's day and night, a shadow created from the sun illuminating half of the spherical moon at any one time. As depicted in the previous section, due to EA we are always observing the nearside (or underside) of the moon.

The curved rays of the sun results in the phases upon the Moon's surface. The plane of the Moon's route is at an inclination to the plane of the Sun's ecliptic, with its highest side opposite from the sun. When the Moon is far from the Sun and higher than it, the Full Moon occurs. When the Moon is closer to the Sun and lower than it, the New Moon occurs1. The Moon moves at a slightly slower rate than the Sun across the sky, causing the range of phases. The time between two Full Moons, or between successive occurrences of the same phase, is about 29.53 days (29 days, 12 hours, 44 minutes) on average.

Sample large-scale sun ray diagram (side view):

Moon Position Table

Compare the above with the following table from Cornell University (Archive), which provides a rule-of-thumb summation for when the Moon rises and sets during its phases:

| Moon phase | Moonrise | Moonset |

|---|---|---|

| New | Sunrise | Sunset |

| 1st quarter | Local noon | Local midnight |

| Full | Sunset | Sunrise |

| 3rd quarter | Local midnight | Local noon |

1 Around the time of the New Moon the Moon is not technically seen. According to Kean University (Archive): “ The New Moon begins the lunar cycle. The age of the Moon in a lunar cycle is measured from the time of New Moon. At New Moon the Earth, Moon and Sun are lined up. Because of the glare of the Sun, the Moon cannot be seen for a few days. After about 3 days, it is possible to see a thin crescent in the West or Southwest at sunset. ”